Mario Grut was born Sept 19th 1930 in Gothenburg. He established himself as a writer, translator, critic, and filmmaker, from the late 1950s and forward based in Sweden until his death in Gotland July 2nd 2007. Mario Grut's identity was complex. He grew up in Thailand, held a Danish passport all his life, and never aspired to "become Swedish". He said he despised nationalism, and rather wanted to be a citizen of the world. His refusal to be identified as Swedish was partly influenced by being exposed to exclusion and bullying in school after arriving in Sweden 1939, because of not speaking Swedish, having black hair and brown eyes, and "a strange name". It was probably also an effect of being forcibly uprooted from his native life and brought to a very different environment in a country to which he never fully managed to adapt. This page is dedicated to Mario Grut's private life. More about his professional achievements will follow. For now, we recommend you to visit Nationalencyclopedin(NE), Svenskt översättarlexikon and Wikipedia.

PRIVATE LIFE

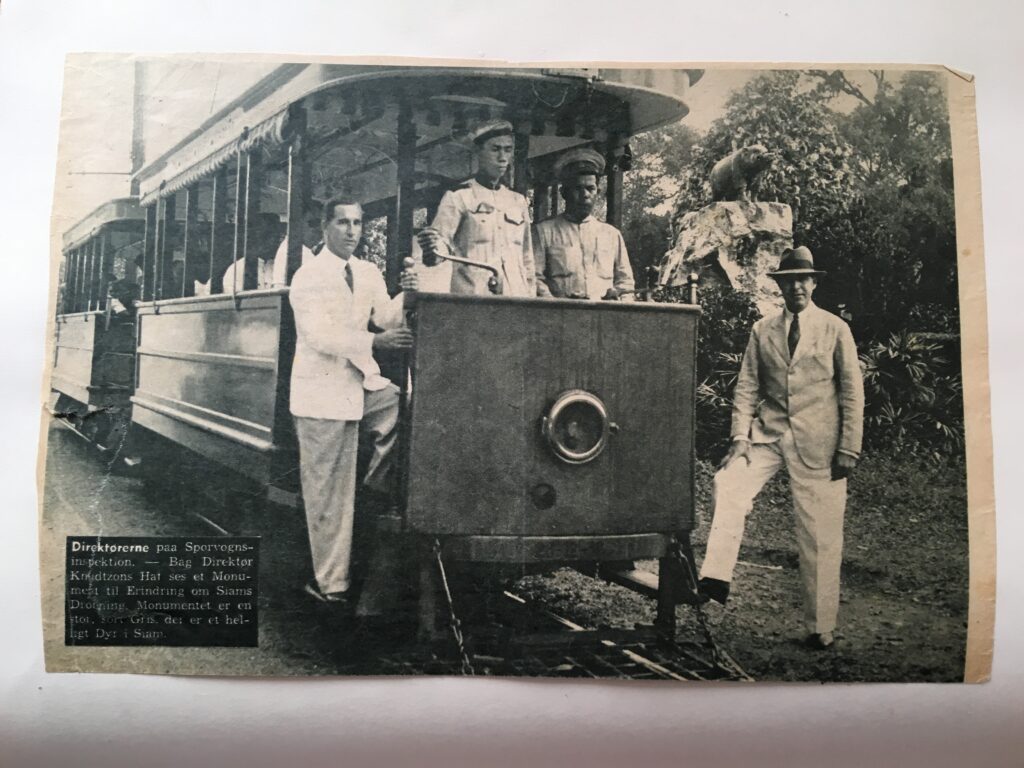

Mario Grut grew up in Thailand, where his Danish father Edmund Tage Grut (1902-1958) was hired in 1924 as Traffic Manager for the Tramways in Bangkok. His Swedish mother, Sigbrit Wijk (1902-1985), hailed from a business family in Gothenburg.

Mario’s first languages were Thai and English, then Swedish from when he arrived in Sweden in 1939 to attend boarding schools in Tällberg and later Sigtuna while the parents remained in Thailand hoping that the war would not reach. His brother Mikael, resident in London, confirms:

"We didn't know one word of Swedish when we arrived. It was tough, we were exposed to a lot of bullying. Thai became our secret language."

.

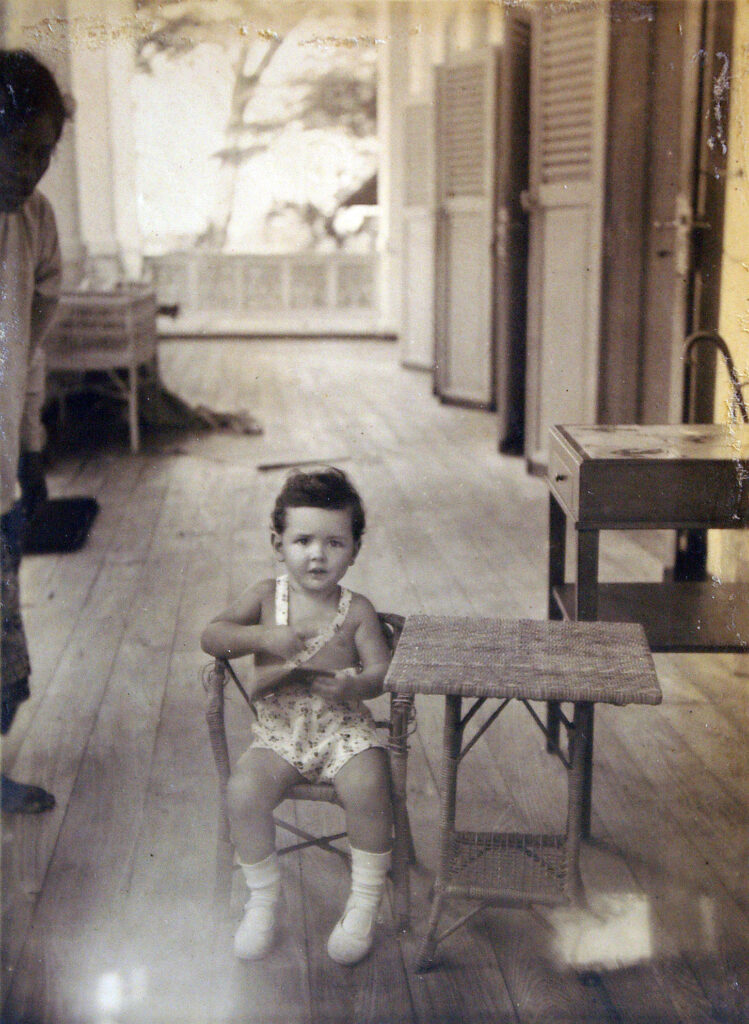

CHILDHOOD

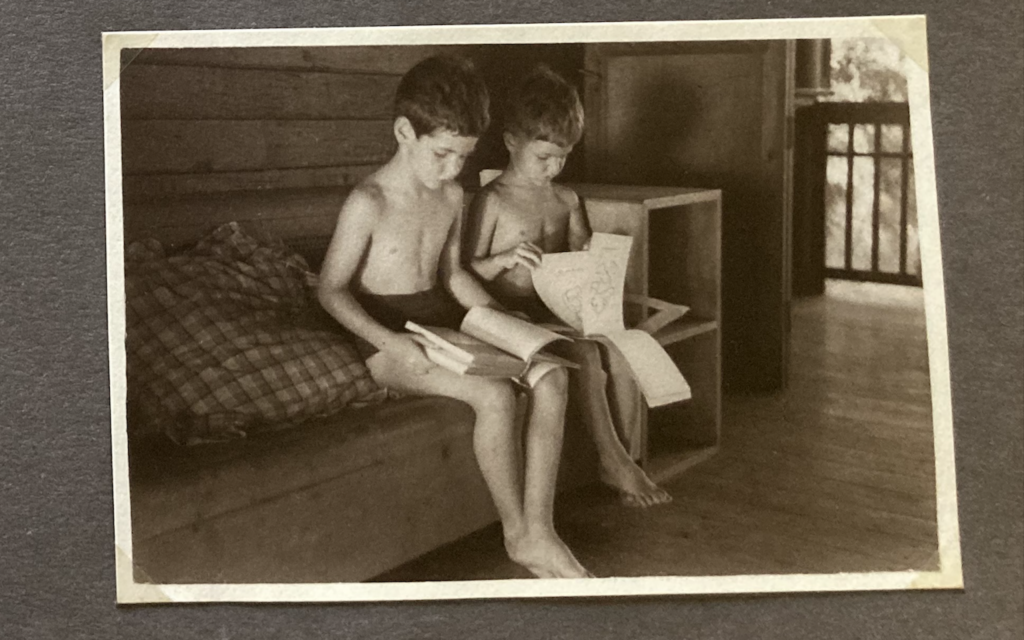

Mario’s early childhood seems to have been very happy and the family lived well, in Khlong Toei in Bangkok. This was before the large port was built. The area was very rural then with waterways, buffalos and rice fields just outside the windows, and large snakes that were a constant danger for the children.

Summers were spent in Ba Noi, where the father owned a traditional Thai sailing boat together with another man, and the children could enjoy wide sandy beaches that were more or less desolate.

Thai, was the language spoken at home with parents and nannies. But when Mario was put in the British Tanglin Boarding School in Malaysia, when he was only 6 years old, he had to learn English.

The boarding school environment was tough. As an adult Mario did not want to talk much about his experiences, but one could sense that being left there all alone by the parents at such a tender age had influenced him a lot. His brother Mikael explains:

"I will never forget when we drove away from Tanglin school, leaving Mario behind. I saw him crying and shouting, held back by staff not to run after us. And I could do nothing."

As mentioned earlier the father Edmund Tage Grut was a Traffic Manager for the Tramways in Bangkok from 1924. According to several sources he served as Honorary Counsel for Sweden during the years 1938-1942* in Thailand (at that time called Siam), and had many diplomatic contacts with the Thai government as well as with Swedish diplomats before, during, and after the war. He was fluent in Thai, Chinese, and English. During WWII he joined the British army and was stationed as an intelligence officer with General Mountbatten’s South East Asia Command 1943-1946, to help gather information about allied war-time and post-war intentions**, and participate in negotiations with the Thai exile government. He has written some (he was under oath not to tell all) about his experiences in his book ”Kina i støbeskeen” which was published in 1947.

*According to the book De Danske i Siam (A. Kann Rasmussen: Danske i Siam 1858-1942. Nyutgiven på Dansk Historisk Handbogsforlag, Kbh. 1986), as well as according to the book Kina i Støbeskeen by Edmund Grut himself, (Gyldendal, 1947).

**According to the book ”OSS, SOE and the Free Thai Underground during World War II” by E. Bruce Reynolds.

.

ADOLESCENCE

Mario Grut was sent to boarding school in Sweden in 1939 together with his brother, maybe by advice from the Danish family that feared a German invasion of Denmark. Their parents, separated by circumstances during the second world war, were not reunited until 1946. That’s when the father came back to Scandinavia after serving in the British army.

From adolescence Mario Grut continued to travel extensively. While his father and mother moved to Denmark when the war and the German occupation was over, Mario was sent to France to better his French. When the father started working as vice president for SAS in Stockholm, with the assignment to establish regular flights to India and Southeast Asia, the family moved to Bromma. In 1949 Mario Grut was noted in the Swedish population register as immigrated from Denmark.

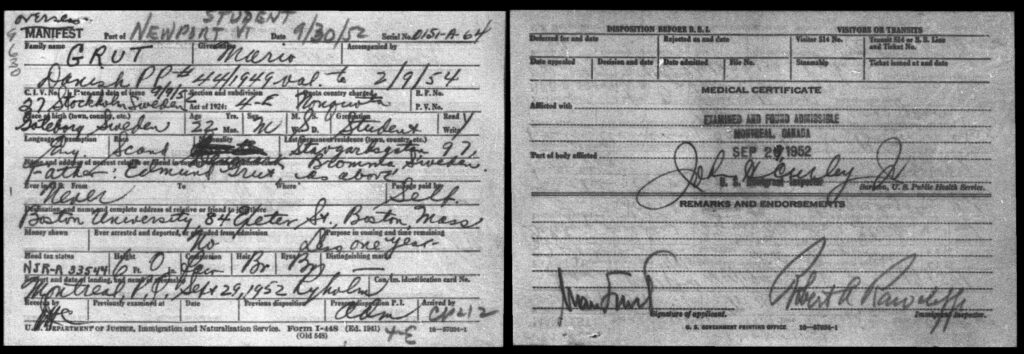

Mario went on to the USA to study at Boston University in 1952 and later traveled in Europe meeting with filmmakers, writers and artists. With time he became a polyglot, fluent in English, Swedish, Danish, French, German and Italian.

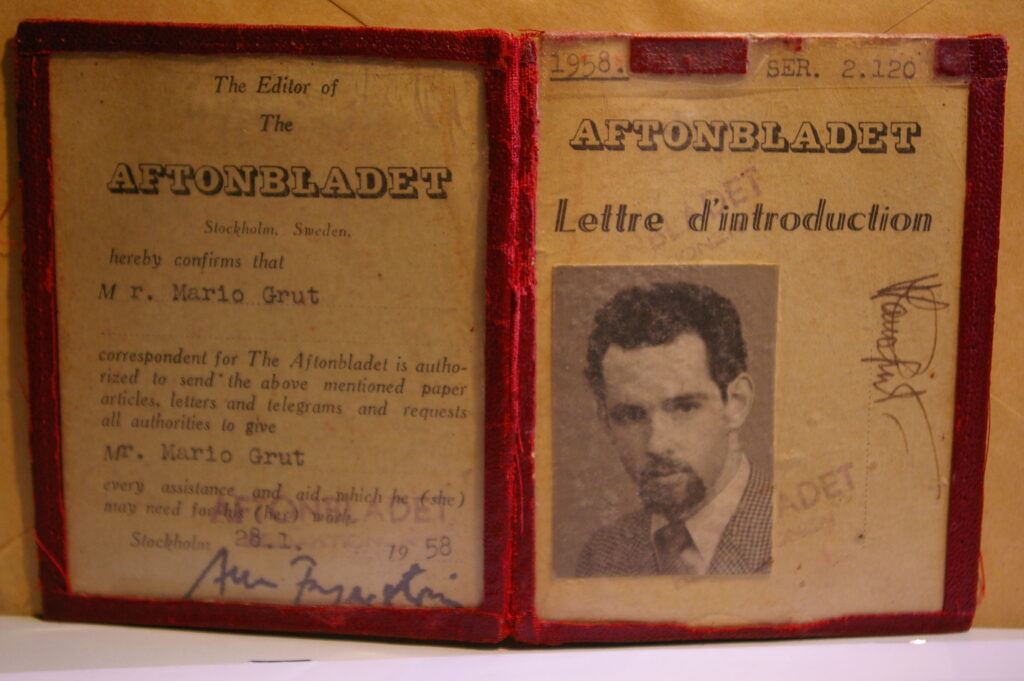

The family moved back to Denmark in 1954. But Mario returned to Sweden, where he was drawn into artist circles, started writing for the theatre, and engaged himself in political debate about culture. In the late 50s he was recruited to write pieces on culture for Aftonbladet by the editor Karl Vennberg, and established himself as a freelance writer and translator with his base in Stockholm, using Swedish as his main language.

He got married in 1958 to the Journalist Birgitta Sundén, and they had three children together, Aminata Merete, Torben and Jannike. But Mario kept on traveling the world, making films, taking photos and writing, for mainly Aftonbladet.

Mario Grut belonged to a generation that expressed they had felt like prisoners during the war, longing to become free to travel, meet new people and explore the world. When the war was over he became one of the post-war cosmopolitan globetrotters, traveling in gentleman style.

He never really managed to settle for a longer time in one place without traveling. And he was never able to fully embrace the Scandinavian winters. Every autumn, when the polar darkness in Sweden became too much for him to bear, the family would see him disappear in his car on long trips to southern Europe. He would not return from his travels until the sun was back and days were longer in March-April. At one point he even spent almost a full year living and writing in Fiesole, a small italian village in the mountains above Firenze.

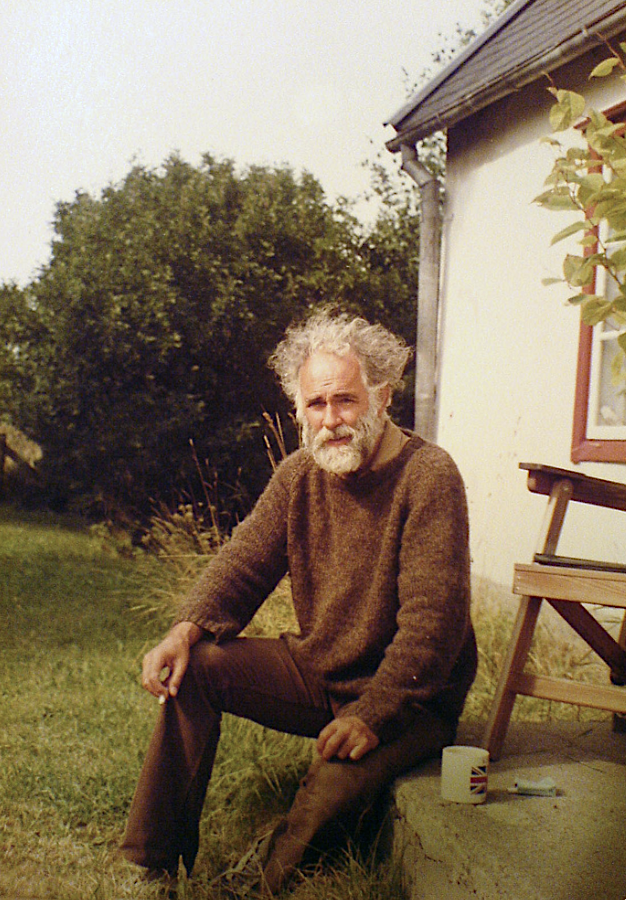

During summertime he would otherwise spend time with his children and keep the shrubs, trees, and pastures around his house in southern Gotland as lush and wildgrown as his hair and beard, probably in part recreating the feeling of the rich rainforests from his childhood.

Never taking the final step into ”Swedishness” through applying for a Swedish citizenship was a conscious decision, he told the family, since he felt that he was not Swedish but rather a citizen of the world. According to him there should be no borders, and nationalism was a dangerous poison that had caused enough destruction and suffering.

True to his word, he kept his Danish citizenship until his death, in Gotland outside his house Barkarve, July 2nd 2007.